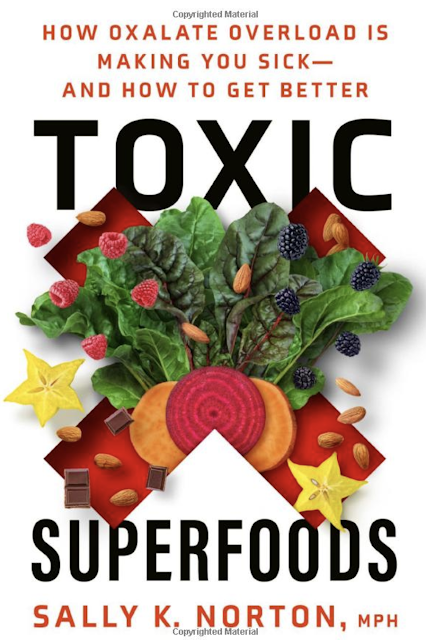

Are These Oxalate-Rich Superfoods Making You Sick?

Oxalates are naturally occurring compounds found in many plant-based foods, such as leafy greens, nuts, seeds, and some fruits. They are also produced by the body.

Oxalates have sparked interest and debate in nutrition circles. While they help plants protect themselves and regulate their minerals, they may undermine human health in complex ways that we don’t yet fully understand.

Scientists have yet to determine a specific purpose for oxalates in the human body, but the fact that we naturally produce them suggests there may be functions we have yet to discover.

For most people, eating oxalate-rich foods as part of a balanced diet does not appear to cause problems. However, mounting evidence suggests that some people, particularly those with certain genetic predispositions or gut health issues, may be at higher risk of health concerns if they eat too many oxalates.

What transforms these compounds into potential troublemakers for some?

The answer may lie in the broader context of our modern lives. Year-round access to high-oxalate foods, increased consumption of processed foods and seed oils, chronic stress, and gastrointestinal dysbiosis may contribute to increased susceptibility to oxalate-related issues in certain individuals.

This is not a case of labeling certain foods as “toxic.” Rather, it’s about understanding the complex interplay between our diets, lifestyles, and individual biochemistry. It’s a reminder that what works for one person may not work for another when it comes to nutrition and health.

A Case Study: Oxalate Overload

Sally Norton, a nutritional science graduate of Cornell University, experienced multiple health issues for more than three decades despite adhering to what she thought was the perfect diet. “I was eating tons of vegetables, lots of leafy greens, tons of nuts, and I was making myself sicker and sicker,” Norton told The Epoch Times. Her symptoms included chronic pain, digestive problems, thyroid dysfunction, arthritis, tendonitis, thin skin, and debilitating fatigue.Despite trying countless treatments, from physical therapy to surgery, Norton’s condition deteriorated to the point where she struggled to read and had to quit her job.

Then she made one dietary change—she eliminated high-oxalate foods—and her health dramatically turned around. “Within days, my sleep improved. Within weeks, my joint pain decreased significantly, my cognitive function returned, and I was able to resume work and enjoy life again,” Norton said.

Norton’s journey reminds us that even seemingly healthy foods can sometimes be the root of unexpected health challenges.

What Are Oxalates?

Oxalic acid is made from vitamin C, oxaloacetate, and glyoxylate. When this acid binds with minerals such as calcium, potassium, or magnesium, it creates compounds called oxalates, such as calcium oxalate, potassium oxalate, or magnesium oxalate. These oxalates can form tiny crystals in the body.Oxalates are considered anti-nutrients because they can interfere with the absorption of essential minerals such as calcium, iron, and magnesium.

Although oxalates are known for their negative effects, they are also naturally produced in the body, suggesting they may have important roles we don’t yet understand.

“Oxalate might be somewhat analogous to ammonia. Ammonia has very important functional purposes. It’s normal to have some ammonia. But if ammonia rises above a certain threshold, then it becomes neurotoxic and could cause fatigue and brain fog. Oxalate may be similar,” Chris Masterjohn, an independent researcher with a doctorate in nutritional sciences, told The Epoch Times.

The key may be in achieving a balance between oxalate production and removal.

“It shouldn’t be the goal to ensure that the body never makes any oxalate,” Masterjohn said. “We don’t want it being synthesized at a rate that is higher than what we can get rid of because, at some point, it rises above a threshold that causes toxicity. And at a slightly higher point, it crosses a threshold that leads to crystallization.”

Is Modern Life Creating an Oxalate Problem?

The impact of oxalates on health has potentially become more prominent due to a convergence of modern factors.Changes in Modern Food Supply

Historically, many high-oxalate foods were only available seasonally. Today, however, foods rich in oxalates, such as spinach and almonds, are available throughout the year.Shifts in Dietary Practices

Americans cooked with animal fats, such as butter and lard, until the advent of vegetable oils in the early 1900s. Today, “the average American is consuming at least one-fourth, and some a third, of their diet as vegetable oils,” according to Dr. Chris Knobbe, known for his research on Westernized diets’ connection to chronic diseases.Vegetable oils, such as soybean, safflower, and sunflower oil, can lead to oxalate production in the body.

“Vegetable oils are rich in a type of fatty acid called polyunsaturated fatty acids,” Masterjohn said. “Those are highly vulnerable to a type of damage that can occur in the body called oxidation. When they oxidize, they break apart into small pieces. One of those small pieces [glyoxal] may undergo several steps of metabolism to become oxalate,” he added.

The Prevalence of Modern Diseases

An estimated 129 million Americans have at least one major chronic disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease can increase oxidative stress levels, “which we believe promotes the generation of more glyoxal (a precursor of oxalate) and its metabolism to oxalate,” according to a 2012 article in Advances in Urology.The Impact of Gut Microbiota on Oxalate Levels

The loss of oxalate-degrading bacteria can lead to increased oxalate levels in the body.Maintaining a healthy gut microbiome may be key in naturally reducing oxalate buildup in the body.

“We are losing microbes that possibly degrade oxalate,” Dr. Sabine Hazan, a physician specializing in gastroenterology and chief executive officer of Progenabiome, told The Epoch Times during a phone interview. “Loss of microbes is the culprit of disease.”

The absence of Oxalobacter formigenes and other oxalate-degrading microbes may partially explain why some people seem more susceptible to oxalate-related problems than others.

Health Conditions Linked to Oxalates

The harmful effects of oxalates have been documented since the 19th century. In 1823, for example, a toxicology study published in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal recognized its toxic effects. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, doctors linked oxalates to a constellation of symptoms beyond kidney stones.- Cardiomyopathy: Crystal deposits can result in arrhythmia, palpitations, syncope, dyspnea, and, in rare instances, chest pain, according to a 2013 article in Current Rheumatology Reports.

- Chronic pain: Deposition in bone, nerve, and muscle cells can cause pain, according to a 2013 article in Current Rheumatology Reports.

- Visual disturbances: Crystal deposits within the retina can lead to vision issues, including glaucoma, cataracts, retinal detachment, and white flecks or spots, according to a 1980 case study in the British Journal of Ophthalmology.

- Arthritis: Oxalate crystals can deposit in joints, causing pain and stiffness like arthritis. In some cases, hyperoxaluria can lead to oxalate arthritis.

- Digestive issues: Oxalates can irritate the lining of the digestive tract, potentially contributing to leaky gut syndrome and other gastrointestinal problems.

- Autoimmunity: Oxalate crystals can trigger inflammation, which could contribute to autoimmune conditions. For example, higher levels of oxalate have been detected in people with celiac disease, according to an article published in the 2016 issue of the Journal of Gluten Sensitivity.

Are Oxalates a Problem for You?

According to Masterjohn, some people have a genetic mutation that increases their tendency to produce oxalates, while others, without the mutation, may still be sensitive to oxalates.- History of repeat antibiotic use or kidney stones

- Digestive disorders such as Crohn’s disease or leaky gut syndrome

- Genetic predisposition to oxalate sensitivity

- Bariatric surgery

- Certain nutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin B6

- Chronic yeast and fungal infections

- Diets high in oxalate-rich foods

- Recurring kidney stones

- Unexplained joint pain or arthritis-like symptoms

- Chronic digestive issues

- Frequent urinary tract infections or bladder pain

- Chronic fatigue or brain fog

- Skin problems like rashes or hives

- Symptoms that worsen after consuming high-oxalate foods

Identifying Oxalate Sensitivity

While there’s no definitive test for oxalate sensitivity, several diagnostic approaches can be useful:- Urinary oxalate testing: Measures oxalate levels in urine, though daily variations can limit accuracy

- Gut bacteria composition testing: Identifies dysbiosis and potential lack of oxalate-degrading bacteria

- Nutrient deficiency testing: Checks levels of vitamin B6, calcium, magnesium, zinc, thiamin, and iron

- Yeast and fungal infection testing: Detects infections that may contribute to oxalate production in the body

How Do You Lower Oxalate Levels?

If you suspect oxalates are affecting your health, there are several strategies to reduce your oxalate load:Calcium sources extend beyond dairy, which is helpful for anyone with a dairy allergy or sensitivity.

“Every traditional culture had some major source of calcium in their diet,” Masterjohn said. “One of the common ones for hunters and gatherers would be bones. Inuit diets are mostly animal products and they don’t have dairy. They saw it as important enough to get their calcium that they would freeze dry and pulverize bones from fish if they lived where they would not have access to fresh fish during certain seasons. The Hadza don’t have milk, but there’s a plant called Baobab, which is very high in calcium, and they consider it a food group.”

- Spinach

- Almonds and cashews

- Peanuts

- Swiss chard

- Chocolate

- Sweet potatoes

- Rhubarb

- Beets

- Black tea

- Chia seeds

- Turmeric

- Black pepper

- Buckwheat

- Amaranth

- Vegetables: Asparagus, arugula, lettuce, bok choy, chives, bell pepper, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, capers, cauliflower, cilantro, celeriac root, cucumber, lacinato or purple kale, mushrooms, onion, radish, rutabaga, turnips, green peas, pumpkin, winter squash, zucchini, watercress, water chestnuts

- Fruits: Apples, avocado, cranberries, grapes, kumquat, mango, papaya, plum, cantaloupe, watermelon, honeydew, lemon, limes, dates, blueberries, olives

- Grains: White rice, oats, corn, barley

Oxalate Release Side-Effects

- Increased joint pain

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Skin rashes or itching

- Mood changes

- Digestive upset

.png)

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment