Plant Based Diet vs Meat: What's the Difference?

The phrases "vegetarian diet" and "carnivore diet" are being tossed around a lot these days.

For some, a "vegetarian diet" is what vegans eat. Veganism combines a diet free of animal products with a moral philosophy that rejects the "commodity status of animals."Vegans are the strictest of vegetarians, avoiding milk, fish, and eggs.

One plant-based diet advocate in the introduction to a special issue of the Journal of Geriatric Cardiology (2017) wrote that "a plant-based diet consists of all minimally processed fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, herbs, and spices and excludes all animal products, including red meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products."

Whole-Foods Version

The so-called documentary "Forks Over Knives" brought the phrase "whole food, plant-based diet" to national prominence. The film focused on the diets espoused by Caldwell Esselstyn and T. Colin Campbell. Since its release in 2011, a whole industry based on the Forks Over Knives (FON) brand has been launched. FON uses the following definition:"A whole-food, plant-based diet is centered on whole, unrefined, or minimally refined plants. It's a diet based on fruits, vegetables, tubers, whole grains, and legumes; and it excludes or minimizes meat (including chicken and fish), dairy products, and eggs, as well as highly refined foods like bleached flour, refined sugar, and oil."

For detailed posts on the Esselstyn diet, check out here and here. However, it is needlessly restrictive and not supported by much scientific evidence. (Esselstyn's website and book state unequivocally "you may not eat anything with a mother or a face" and "you cannot eat dairy products," which differs from the FON (Fork over Knives) definition.)

The key new terms to note in the FON approach are:

- Whole food, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "food that has been processed or refined as little as possible and is free from additives or other artificial substances."

- Unrefined or minimally refined, with refined defined by that dictionary as "impurities or unwanted elements having been removed by processing."

The FON definition for a plant-based diet then is similar to our first definition -- minimally processed vegan -- but allows (at least theoretically) minimal meat, dairy and eggs. The FON Esselstyn/Campbell diets choose to define vegetable oil, including olive oil, as highly-refined foods and do not allow any oils.

Diet Ranking Definition and the Mediterranean Diet

U.S. News and World Report publishes an annual rating of diets based on the opinion of a panel of nationally-recognized experts in diet, nutrition, obesity, food psychology, diabetes and heart disease.

That publication defines a plant-based diet as "an approach that emphasizes minimally processed foods from plants, with modest amounts of fish, lean meat and low-fat dairy, and red meat only sparingly."

Notice now that you can have "modest amounts" of meat and dairy, foods that are anathema to vegans. Also, note that "low-fat dairy" is being recommended, which involves processing and adulterating what are in my opinion healthy natural dairy fat foods, making it highly processed. Lean meat is preferred, and red meat avoided.

Plant Based Diet vs Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet ranked as U.S. News' best diet overall. However, the Mediterranean diet came out on top of the list of "Best Plant-Based Diets."The plant-based diet of vegans or of "Forks Over Knives" is drastically different from the Mediterranean diet.

For example, olive oil consumption is emphasized in the Mediterranean diet, whereas the Esselstyn diet featured in FON forbids any oil consumption.

The FON/Esselstyn diets are very low in any fats, typically <10%, whereas the Mediterranean diet is typically 30% to 35% fat.

Esselstyn really doesn't want you to eat nuts and avocados, because he thinks the oil in them is bad for you. However, nuts were given to the participants in the PREDIMED randomized trial showing the benefits of the Mediterranean diet.

The Mediterranean diet promote fish consumption as a great way to get more protein. But consumption of fish can have its risks, too, a point Tony Robbins made in an interview with Men's Journal:

The Ornish Diet-Still Not Proven to “Reverse Heart Disease”

Dr Anthony Pearson (The Sceptical Cardiologist) has critiqued in detail Dean Ornish’s claims to have scientific proof that his diet/exercise/meditation program “reverses heart disease” here. The bottom line is that these claims are not supported and that is why his program is not recommended by the AHA or the US Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

He was pleased to see that the Ornish diet has slipped from #3 to #4 in the US News and World Report overall best diet recommendations for 2020. However, the Ornish diet seems to have risen to #1 for “heart-healthy diets” something I strongly disagree with.

The blurb associated with Ornish states “ranked highly for heart health again this year due to its holistic and evidence-based approach shown to help prevent and even reverse heart disease.”

It is not evidence-based and it is holistic in the sense that a regular exercise plan and stress mediation is part of the program, something that should be part of any lifestyle approach to heart disease.

Dr. Pearson’s Plant-Based Diet

With the Dr. P Plant-Based Diet© “your primary focus in meal planning is to make sure that you are regularly consuming a large and diverse amount of healthy foods that come from plants."

If you don’t make it your focus, it is too easy to succumb to all the cookies, donuts, pies, cakes, pretzels, chips, French fries, breakfast bars and other calorie-dense but nutrient-light products that are cheap and readily available.

In Dr. P’s Plant-Based Diet© meat, eggs, and full fat dairy are on the table. They are consumed in moderation and they don’t come from plants (i.e. factory farms).

Definition:

- Regularly = at least daily.

- Large amount = 3 to 4 servings daily.

- Healthy = a highly contentious term and one, like “plant-based” that one can twist to mean whatever one likes.

Dr. P is not a fan of plant-based margarines, added sugar, whether from a plant or not, should be avoided, and the best way to avoid added sugar is to avoid ultra-processed foods.

Ultra-processed foods (formulations of several ingredients which, besides salt, sugar, oils and fats, include food substances not used in culinary preparations, in particular, flavours, colours, sweeteners, emulsifiers and other additives used to imitate sensorial qualities of unprocessed or minimally processed foods and their culinary preparations or to disguise undesirable qualities of the final product).

Ultra-processed foods account for 58% of all calories in the US diet, and contribute nearly 90% of all added sugars.

Vegans need to stop exaggerating the health benefits of a plant-based diet

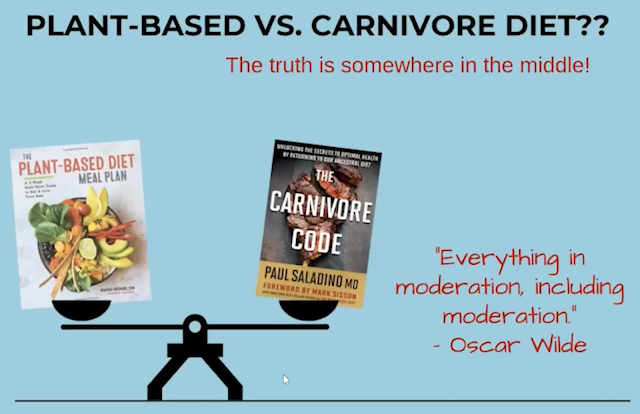

On the internet, you’ll find extreme dieters of all types, and many of them will swear to you that theirs is the only healthy way for a human to eat. At one end of the spectrum, there’s Jordan Peterson with his carnivore diet, consisting of nothing but beef, salt and water. At the other, “frugivore” diets pushed by YouTubers and their ilk are not just vegan and raw but almost entirely made up of fresh fruit. And then, of course, we have the classic and unapologetically restrictive weight loss programs like the cabbage soup diet, the Master Cleanse (aka the lemonade diet), and the currently trendy Mono Diet, where you eat only one food.

Advocates for highly restrictive diets like these tend to massively overemphasize the benefits of their approved food while seriously exaggerating the drawbacks of all other foods. But these are only the most extreme examples of a supposed “wellness” culture that makes huge generalizations and routinely manipulates or straight-up ignores scientific evidence. Unfortunately, this approach ends up polluting even those conversations that do have some legitimate basis—for instance, veganism.

There are plenty of health benefits to a plant-based diet, and unlike the above examples, it’s not even necessarily a particularly restrictive diet—even nonvegans and nonvegetarians who eat primarily plant-based can reap the benefits. But the unfortunate truth is that like most things on the internet, a grain of truth gets stretched far beyond the bounds of what science can actually prove.

It’s not hard to imagine why some voices for veganism might exaggerate or even fabricate health-related claims. The animal agriculture industry enacts gruesome violence against animals, as well as many of its laborers and, of course, the health of the planet. So if health is what will compel people to change their diets in a way that’s beneficial for animals and the environment, it’s easy to see why some activists and influencers would push nutritional facts as the most effective avenue to help end the industry.

But ultimately, misinformation is only going to harm the movement’s credibility. Veganism is a more widespread idea in our society now than ever before—we can’t afford to risk causing folks to dismiss the whole thing as bunk. And all of this misinformation, exaggeration, and cherry-picking is a shame, because it obscures the actual strong evidence of the benefits of eating less meat, eggs, or dairy: lower risk of heart disease, stroke, and several types of cancer, to name just a few.

Regrettably, conversations around veganism tend to be rife with pseudoscience. It’s not hard to find vegan influencers who spout unproven theories as though they were fact, utilize confusing and misguided logic, or say things that are plainly false—like that a vegan diet can change your eye color. Even actual medical doctors have been known to make dramatic and shaky claims, such as that a single meal high in animal fat can “cripple” a person’s arteries, citing one single, decades-old study that featured just 10 subjects and no control group.

You’ll hear people saying that nothing less than a 100% plant-based diet can be considered optimally healthy, when the reality is, we just don’t have the data to back that up. Sure, there are plenty of studies that do support the general idea that plant-based eating is healthy in one way or another, and plenty of them are recent and use reliable methodologies. But even good data can be woefully misinterpreted. Correlation often gets mistaken for causation, and it’s difficult—if not impossible—to isolate very specific inputs and outcomes (like, does cheese cause cancer?) because human biology and lifestyles are complicated.

Here’s an example: James Beard Award-winning Washington Post columnist Tamar Haspel points to this Bloomberg article, the headline of which boldly claims, “One Avocado a Week Cuts Risk of Heart Disease by 20%.” Which sounds huge! But a closer look reveals that the study only demonstrates an association between avocados and heart disease, not a causal relationship. Do avocados cut the risk of heart disease, or do people who make overall heart-healthy lifestyle choices just eat a lot of avocados? Based on this study alone, we can’t say. Any conclusion is, at best, a loose interpretation of the facts.

The Carnivore Diet

When Saladino discovered the carnivore diet, he'd already been contemplating ancestral norms and evolutionary ideas, asking questions such as: "Where have humans come from? How do we eat? What is the most congruent way of eating for humans that is going to give us optimal health?"

He admits the idea of the carnivore diet is “super radical.” He first heard of the carnivore diet from Jordan Peterson on a Joe Rogan podcast. He talked about his daughter Mikhaila, who had a bad case of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), which is an autoimmune inflammatory disease.

She had multiple joint replacements at a young age, which crippled her. "She discovered this way of eating only animal meat," Saladino says, and over time, her symptoms improved.

"In medicine, we talk about case reports. I love case reports because I want to see how things actually work at a real level," Saladino says. "It was so striking to me that someone like Mikhaila could essentially reverse and completely heal from JRA and then the depression that was connected with it, probably because of the concomitant immunologic and inflammatory mechanisms with this radical dietary change.

I thought, 'That is really striking. I want to study that.' Then Jordan Peterson talks about the fact that he had anxiety and sleep apnea and other issues himself. They improved when he started eating an animal-based diet."

Might Plant Diets Trigger Autoimmune Problems in Some People?

"I love that this notion just turned it all on its head. It just tipped everything over and I thought, 'Wait a minute. It kind of makes sense. Maybe plants don't want to get eaten. Maybe plants aren't good for humans?' At the beginning, I was very skeptical and I thought, 'I really need to dig into this,' and so I did …

This fundamental premise, this idea that plants and humans, plants and herbivores or plants and animals have coevolved, and every life form really has one goal. That's to push its DNA into the next species and to continue the lineage of that species.

A mustard plant wants the mustard plant to continue. An oak tree wants the oak tree to continue. Life and ecology is this beautiful intermingling of all these species working together but fighting and eating each other and trying to kill each other, but sometimes being symbiotic.

This concept that 'Maybe plants don't want to get eaten after all,' maybe this unconditional narrative that all plants are good for you all the time, maybe we should question that. That's a pretty radical concept, because I think even within the functional medicine sphere, there's this notion that all plants are good for you and the more plants you eat, the better.

But this counterculture, disruptive concept that for some people — perhaps for all of us, perhaps just for some people — plants can trigger autoimmunity through a variety of mechanisms is really intriguing."

Read More: Could Eating Like a Carnivore Wreck Your Health

Conclusion

The issues with nutritional science as we know it today go even deeper. For one thing, many of these studies (including the avocado one) rely on self-reported information from study participants. That’s putting a lot of faith in regular people to accurately and honestly measure their own eating habits, which human beings are famously bad at. When the input data is already in question, it’s hard to trust any conclusions drawn from it.

Even putting that aside, observational studies don’t allow scientists to randomize their study subjects. If we’re just noting what real people are actually doing, we can’t separate the elements we want to examine—for instance, meat consumption—from other factors like income, education, gender, smoking and drinking behavior, and what else they eat. As a result, the kind of information we get from these studies is imprecise; and unless the results include very dramatic, statistically significant trends, it’s risky to extrapolate much from them.

But getting the kind of data we could reliably work with is more or less impossible. To truly control a study, researchers would have to literally control everything eaten by hundreds of participants (or more) over a period of years, in order to eliminate all (or even most) potential confounding factors. Real human lives are just too complicated to regiment the way a true lab study requires.

Furthermore, the biological world is just more complicated than we’d like to think. Different people have different nutritional needs. For people with certain gastrointestinal conditions, eating fully vegan just isn’t feasible. But even barring that, human bodies are unique and one person may not process a particular food in the exact way another person would. With that in mind, one-size-fits-all health advice of any kind should probably be subject to some heavy skepticism.

Given all of this, it’s no wonder that doctors, nutritionists, researchers, and other credentialed experts—not to mention third party interpreters of research, like journalists and other media figures—tend to give diverse, often contradictory advice.

Meanwhile, an alarming portion of the population, and even of the scientific community, are apparently indifferent to nutritional science altogether. Fewer than 20% of medical schools in the U.S. have a single required course on nutrition, and the majority of medical schools teach less than 25 hours of nutrition education in the four years it takes to complete an MD program. All this, despite the fact that diet-related disease—much as heart disease and type 2 diabetes—are among the leading causes of death in the U.S. today.

Our diet-obsessed culture is constantly searching for a magic bullet to fix all the diet-related problems we face. We try complicated, often punishing, and sometimes even dangerous methods to, ostensibly, “get healthy” (often a euphemism for “lose weight”), based on so-called empirical evidence that’s shaky at best.

The fact is, nutritional science just isn’t at a point where we can confidently dole out sweeping directives on how people should eat. Sure, there are some points that the medical community has reached some degree of consensus on: The American Heart Association tells us that “eating a lot of meat is not a healthy way to lose weight,” especially for folks who have or are at risk for heart disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says to avoid processed food and sugary drinks in order to lower our risk of heart disease and stroke. And the American Cancer Society tells us to eat a variety of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

Based on the following References:

Mikhaila Peterson Fuller stepped onto the historic Oxford Union stage and silenced the entire room with an 8-minute speech.

— Camus (@newstart_2024) December 6, 2025

The motion being debated: “This House Would Move Beyond Meat.”

She spoke against it — and started with this:

“At age 7 I was diagnosed with juvenile… pic.twitter.com/2hOSj02QUh

.png)

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment