Mavenclad Is a Miracle for Multiple Sclerosis, but Only if You Can Afford It - New York Times

April Crawford never thought she’d be begging for help on GoFundMe, but she has run out of options. She has multiple sclerosis, and Mavenclad, the drug that could slow her decline, has a list price of $194,000 a year. Her Medicare insurance will pay for most of it, but she has a co-pay of $10,000.

Ms. Crawford, 47, doesn’t have $10,000 and has no way to get it. A law signed last year will put a $2,000 annual limit on out-of-pocket costs for Medicare patients like her — but not until 2025. Even at that price, money is tight in her household. She and her husband, who is disabled with COPD, live in Oliver Springs, Tenn., with a nephew who was disabled by a traumatic brain injury. All three of them rely on federal disability payments.

So she posted an appeal on GoFundMe in August. At the time this article was published, she had raised $20.

Ms. Crawford has come face to face with a persistent dilemma in medical care. Advances in science and immense investments by the federal government and drug companies have completely altered prospects for people with conditions that seemed untreatable in almost every area of medicine — cancers, allergies, skin diseases, genetic afflictions, neurological disorders, obesity.

“This is the golden age of drug discovery,” said Dr. Daniel Skovronsky, chief scientific and medical officer of Eli Lilly and Company, which has new treatments for obesity, mantle cell lymphoma and Alzheimer’s.

Prices reflect the inherently costly and fundamentally different way drugs are developed and tested today. But, he said, the burden on patients who cannot afford life changing new drugs weighs heavily on him and others who work for drug companies.

For many people using private insurance, innovative medicines are dangling just out of reach. Even when Medicare’s 2025 cap comes into play — or the $9,100 cap that already existed for those receiving insurance under the Affordable Care Act — many will still find drugs unaffordable. Research suggests large numbers of patients abandon their prescriptions when faced with $2,000 in payments.

One telltale sign that a treatment is working, experts say, is a widening chasm in outcomes between wealthy patients and everyone else. This is in part because when the prices for miracle drugs reach hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, many people do not fill prescriptions simply because they cannot afford them.

Underlying the data that quantify these problems are individual stories about patients, like Ms. Crawford, who have tried desperately to find a way to pay for expensive drugs that could make a big difference in their lives. A few have succeeded, often briefly and tenuously, while many others do not. And those experiences produce consequences — cures only for a select few.

Costly Cures

The new era in treating previously intractable diseases began with huge scientific leaps after the turn of the century, allowing researchers to find genes they could target to treat cancers and other diseases. Scientists could harness the immune system or suppress it and even alter patients’ very DNA with gene therapy.

“Today’s drugs are more effective because they target the biology of disease ,” said Dr. Skovronsky of Eli Lilly, with few side effects.

He called previous drugs to treat diseases like psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis “blunt instruments” that shut down the immune system but had serious side effects.

“Yesterday’s drugs were moderately effective in treating a broader population,” he added.

But the drugs that have emerged often are extremely expensive to produce. At Lilly, Dr. Skovronsky said, the company will be spending more than $8 billion in 2023 on drug research and development.

“Some of that money goes to failures, some goes to basic research, some goes to clinical trials and some goes to drugs that actually work,” he said.

Not only are the new drugs costly to research and develop but some treatments are for just a few patients with very rare diseases and some, like gene therapy, are used only once rather than over a person’s lifetime.

The prices of today’s remedies reflect all those factors.

Researchers for Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts found that the median price of a new drug was around $180,000 in 2021, up from $2,100 in 2008.

Those high prices are a factor in a stark wealth gap in medical outcomes. Dr. Otis Brawley, a professor of oncology and epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, points to cancer, where the death rate for Americans with college educations, a proxy for wealth, is 90.9 per 100,000 per year. For those with a high school education or less, the rate is 247.3.

Out-of-pocket costs can run to thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. Often, even those who can afford commercial health coverage or get it through their employer may face insurers that refuse to pay. Other times, an insurer pays part of the cost, but high co-pays, deductibles and cost sharing put treatments out of reach for many.

Some doctors agonize over balancing their responsibility to prescribe effective treatments with anxieties about the financial burdens on patients.

“The idea that the care you deliver could bankrupt somebody and hurt an entire family is devastating,” said Dr. Benjamin Breyer, a reconstructive urologist at the University of California, San Francisco who has studied this issue.

The problem also affects those with Medicaid — which does not always pay for expensive drugs — and Medicare. Medicare Part D helps to pay for prescription drugs for about 50 million Americans, most of whom are older than age 65. Federal data show that the number of extremely expensive drugs Medicare patients take have more than tripled in less than a decade. Some enrollees with incomes below a set level can qualify for subsidies. Although the Inflation Reduction Act requires drug makers to refund price increases above the inflation rate to the federal government, it does not protect patients from prices that are already high.

In 2020, Medicare data included more than 150 brand-name drugs with a cost of at least $70,000 a year to the program — about the average household income for a family. In 2013, adjusting prices for inflation, there were only 40 such drugs.

Today’s ultraexpensive drugs include not just new medications, like Mavenclad, the multiple sclerosis drug that Ms. Crawford needs, but also older medications that drug companies have hiked the prices of in the last few decades.

One example is Revlimid, which treats blood cancers. Its sticker price is three times as high as it was when first introduced in 2005.

As with commercially insured patients, people enrolled in Medicare Part D pay a fraction of that total cost — but as the sticker price rises, so does their out-of-pocket burden. A study by GoodRx found that the average out-of-pocket costs for Medicare patients taking Revlimid was more than $17,000 in 2021.

Jalpa Doshi, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, reports that the high out-of-pocket costs for expensive new drugs have led to many people not filling prescriptions or getting refills, whether they are on Medicare or have private insurance.

With oral cancer medicines, including ones that can change the prognosis for patients, Dr. Doshi studied how out-of-pocket costs for the drugs — co-pays, coinsurance and deductibles — affected use of the drugs. Among those whose payments per prescription were less than $10, 10 percent abandoned their prescriptions. But about 50 percent who had to pay more than $2,000 did so. In the large group of patients she studied — around 38,000 — many had out-of-pocket costs above $500 for their first anticancer medication, and more than one in 10 had costs above $2,000.

“It’s a lethal combination — a high deductible, high coinsurance and a disease that requires a really expensive drug,” Dr. Doshi said.

A separate study of Medicare beneficiaries also found high levels of prescription abandonment — from 20 percent to 50 percent — among patients who did not qualify for subsidies and were given new prescriptions for drugs to treat cancer, hepatitis C and immune system disorders.

In other words, sick people skip treatment, even lifesaving treatment, when it costs them too much out of pocket.

‘6,000 a Month Would Ruin Us’

Bad as it is for Medicare patients, it is even worse for people with private insurance, Dr. Doshi said.

She noted that among households whose members were not old enough to qualify for Medicare, nearly one in three people who live alone and about one in five families did not have enough money to pay even $1,000 in out-of-pocket expenses.

Thousands, like Ms. Crawford, desperately searching for a way to pay for medications, have turned to GoFundMe. But most do not get nearly enough in donations, Dr. Breyer noted.

In one study, Dr. Breyer and his colleagues looked at the GoFundMe experiences of people with kidney cancer, a disease with transformative but expensive treatments. The median goal on the website was $10,000. Just 8 percent reached their goal, with $1,450 being the median amount raised.

Then there is the issue of formularies — the list of drugs an insurer will pay for. If a drug is not on a formulary, patients have to pay the full price or substitute another drug, if one is available, which may not work nearly as well. Patients may also try to appeal the insurer’s decision or apply to a company’s patient assistance program.

Scott Matsuda was hit with the formulary problem when his doctor prescribed him a new drug to treat myelofibrosis, a rare type of chronic leukemia. For years, before the drug was developed, his insurance paid for a cocktail of chemotherapy drugs that did little to slow the course of his disease and caused difficult side effects like severe mouth sores.

Then, he entered a clinical trial of Jakafi, a pill that markedly slowed his disease. He did not notice any side effects.

“It was amazing,” Mr. Matsuda said. “I was really happy.”

Three months later, the trial ended, and the F.D.A. approved Jakafi. The daily pills that were saving his life cost $6,000 a month, but Jakafi was not on his insurer’s formulary.

“We were dumbfounded,” Mr. Matsuda said. He and his wife, Jennifer, have a photography business near Seattle, but that price was totally beyond them.

“We are solidly middle-class,” Mr. Matsuda said. “We pay all our bills. We have a good credit score. Six thousand a month would ruin us.”

He went without medications for a few months but eventually returned to the chemotherapy cocktail, suffering fatigue, agonizing bone pain, nausea and mouth sores on top of the steady progression of his leukemia.

He was saved by his oncologist, who suggested that he apply to the PAN Foundation, which helps people with crushing medical bills.

The PAN Foundation assists patients with an annual income about 4 to 5 times the federal poverty level, said Amy Niles, the foundation’s chief advocacy and engagement officer. Those patients, she said, are “usually people who don’t have high incomes, who are falling through the cracks.” The foundation — supported by individuals, charities and drug companies, which can give to a general program but not in order to pay for their own drug — raises hundreds of millions of dollars a year and helps people with any of about 70 illnesses. But the need is so great, Ms. Niles said, “that we are just scratching the surface.”

Patients say they explore every avenue to find help with their medication bills.

Joan Powell, 69, has myelodysplastic syndrome. She said she hunts for foundations and applies for grant after grant because there is no other way to pay for her Reblozyl prescription, which costs $196,303 a year. She said she is on Medicare, which covers most of the price, but she is left with an annual deductible of $8,925. Her yearly income from Social Security and a pension from a company where she used to work adds up to $36,000. She is unable to work.

So far, she has managed to patch together foundation grants, but she worries about how long she can keep that up.

“People just don’t know what you go through,” she said. “If you think about it too much, you get depressed.”

Doctors say they try to help with appeals to insurers, but they do not always succeed.

Dr. Kari Nadeau, an allergist at Stanford Medicine, said the advent of truly effective drugs to treat severe allergies and disfiguring eczema has been bittersweet.

“The world is full for me now, full of hope and promise,” she said. “I can give a patient a biologic and literally see the skin get better right before my eyes.”

But she has spent hours on the phone trying to convince insurers to pay for some of these drugs, with mixed success. And her patients are among the few with resources to seek out a specialist like her.

Harry Levine, an emeritus sociology professor from Queens College, found an unusual way to pay for his drug for the atopic dermatitis, or eczema, that covers most of his body when untreated.

The only thing that helped was steroid creams, but they were not safe to take continuously. So he went through cycles of getting some relief only to watch his eczema return.

Then, in 2017, his doctor told him about, Dupixent, a stunningly effective new drug.

But it cost $36,000 a year, and his insurance would not pay.

Eventually, he was referred to Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who had led studies of the drug and gets samples from the manufacturer, Regeneron. She provides them to Mr. Levine.

But her clinic is self-pay only. Mr. Levine visits her office every two weeks, pays $325 for the visit, and gets a shot — there is no charge for the drug itself. His eczema vanished.

“My skin is now unblemished,” he said. “It’s a miracle.”

Still, $650 a month?

“It’s a heck of a lot cheaper than $36,000 a year,” he said.

Related: Multiple Sclerosis and Food: Dietary Foes and Friends

Ms. Crawford, 47, doesn’t have $10,000 and has no way to get it. A law signed last year will put a $2,000 annual limit on out-of-pocket costs for Medicare patients like her — but not until 2025. Even at that price, money is tight in her household. She and her husband, who is disabled with COPD, live in Oliver Springs, Tenn., with a nephew who was disabled by a traumatic brain injury. All three of them rely on federal disability payments.

So she posted an appeal on GoFundMe in August. At the time this article was published, she had raised $20.

|

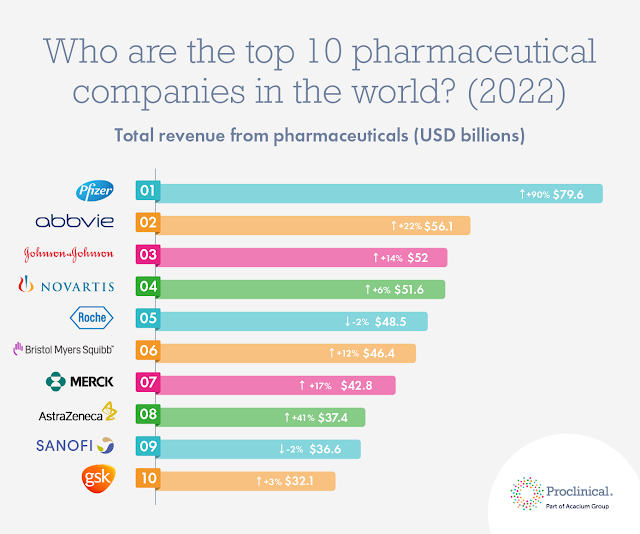

| Credit: ProClinical.com |

Ms. Crawford has come face to face with a persistent dilemma in medical care. Advances in science and immense investments by the federal government and drug companies have completely altered prospects for people with conditions that seemed untreatable in almost every area of medicine — cancers, allergies, skin diseases, genetic afflictions, neurological disorders, obesity.

“This is the golden age of drug discovery,” said Dr. Daniel Skovronsky, chief scientific and medical officer of Eli Lilly and Company, which has new treatments for obesity, mantle cell lymphoma and Alzheimer’s.

Prices reflect the inherently costly and fundamentally different way drugs are developed and tested today. But, he said, the burden on patients who cannot afford life changing new drugs weighs heavily on him and others who work for drug companies.

For many people using private insurance, innovative medicines are dangling just out of reach. Even when Medicare’s 2025 cap comes into play — or the $9,100 cap that already existed for those receiving insurance under the Affordable Care Act — many will still find drugs unaffordable. Research suggests large numbers of patients abandon their prescriptions when faced with $2,000 in payments.

One telltale sign that a treatment is working, experts say, is a widening chasm in outcomes between wealthy patients and everyone else. This is in part because when the prices for miracle drugs reach hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, many people do not fill prescriptions simply because they cannot afford them.

Underlying the data that quantify these problems are individual stories about patients, like Ms. Crawford, who have tried desperately to find a way to pay for expensive drugs that could make a big difference in their lives. A few have succeeded, often briefly and tenuously, while many others do not. And those experiences produce consequences — cures only for a select few.

Costly Cures

The new era in treating previously intractable diseases began with huge scientific leaps after the turn of the century, allowing researchers to find genes they could target to treat cancers and other diseases. Scientists could harness the immune system or suppress it and even alter patients’ very DNA with gene therapy.

“Today’s drugs are more effective because they target the biology of disease ,” said Dr. Skovronsky of Eli Lilly, with few side effects.

He called previous drugs to treat diseases like psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis “blunt instruments” that shut down the immune system but had serious side effects.

“Yesterday’s drugs were moderately effective in treating a broader population,” he added.

But the drugs that have emerged often are extremely expensive to produce. At Lilly, Dr. Skovronsky said, the company will be spending more than $8 billion in 2023 on drug research and development.

“Some of that money goes to failures, some goes to basic research, some goes to clinical trials and some goes to drugs that actually work,” he said.

Not only are the new drugs costly to research and develop but some treatments are for just a few patients with very rare diseases and some, like gene therapy, are used only once rather than over a person’s lifetime.

The prices of today’s remedies reflect all those factors.

Researchers for Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Massachusetts found that the median price of a new drug was around $180,000 in 2021, up from $2,100 in 2008.

Those high prices are a factor in a stark wealth gap in medical outcomes. Dr. Otis Brawley, a professor of oncology and epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, points to cancer, where the death rate for Americans with college educations, a proxy for wealth, is 90.9 per 100,000 per year. For those with a high school education or less, the rate is 247.3.

Out-of-pocket costs can run to thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. Often, even those who can afford commercial health coverage or get it through their employer may face insurers that refuse to pay. Other times, an insurer pays part of the cost, but high co-pays, deductibles and cost sharing put treatments out of reach for many.

Some doctors agonize over balancing their responsibility to prescribe effective treatments with anxieties about the financial burdens on patients.

“The idea that the care you deliver could bankrupt somebody and hurt an entire family is devastating,” said Dr. Benjamin Breyer, a reconstructive urologist at the University of California, San Francisco who has studied this issue.

The problem also affects those with Medicaid — which does not always pay for expensive drugs — and Medicare. Medicare Part D helps to pay for prescription drugs for about 50 million Americans, most of whom are older than age 65. Federal data show that the number of extremely expensive drugs Medicare patients take have more than tripled in less than a decade. Some enrollees with incomes below a set level can qualify for subsidies. Although the Inflation Reduction Act requires drug makers to refund price increases above the inflation rate to the federal government, it does not protect patients from prices that are already high.

In 2020, Medicare data included more than 150 brand-name drugs with a cost of at least $70,000 a year to the program — about the average household income for a family. In 2013, adjusting prices for inflation, there were only 40 such drugs.

Today’s ultraexpensive drugs include not just new medications, like Mavenclad, the multiple sclerosis drug that Ms. Crawford needs, but also older medications that drug companies have hiked the prices of in the last few decades.

One example is Revlimid, which treats blood cancers. Its sticker price is three times as high as it was when first introduced in 2005.

As with commercially insured patients, people enrolled in Medicare Part D pay a fraction of that total cost — but as the sticker price rises, so does their out-of-pocket burden. A study by GoodRx found that the average out-of-pocket costs for Medicare patients taking Revlimid was more than $17,000 in 2021.

Jalpa Doshi, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, reports that the high out-of-pocket costs for expensive new drugs have led to many people not filling prescriptions or getting refills, whether they are on Medicare or have private insurance.

With oral cancer medicines, including ones that can change the prognosis for patients, Dr. Doshi studied how out-of-pocket costs for the drugs — co-pays, coinsurance and deductibles — affected use of the drugs. Among those whose payments per prescription were less than $10, 10 percent abandoned their prescriptions. But about 50 percent who had to pay more than $2,000 did so. In the large group of patients she studied — around 38,000 — many had out-of-pocket costs above $500 for their first anticancer medication, and more than one in 10 had costs above $2,000.

“It’s a lethal combination — a high deductible, high coinsurance and a disease that requires a really expensive drug,” Dr. Doshi said.

A separate study of Medicare beneficiaries also found high levels of prescription abandonment — from 20 percent to 50 percent — among patients who did not qualify for subsidies and were given new prescriptions for drugs to treat cancer, hepatitis C and immune system disorders.

In other words, sick people skip treatment, even lifesaving treatment, when it costs them too much out of pocket.

‘6,000 a Month Would Ruin Us’

Bad as it is for Medicare patients, it is even worse for people with private insurance, Dr. Doshi said.

She noted that among households whose members were not old enough to qualify for Medicare, nearly one in three people who live alone and about one in five families did not have enough money to pay even $1,000 in out-of-pocket expenses.

Thousands, like Ms. Crawford, desperately searching for a way to pay for medications, have turned to GoFundMe. But most do not get nearly enough in donations, Dr. Breyer noted.

In one study, Dr. Breyer and his colleagues looked at the GoFundMe experiences of people with kidney cancer, a disease with transformative but expensive treatments. The median goal on the website was $10,000. Just 8 percent reached their goal, with $1,450 being the median amount raised.

Then there is the issue of formularies — the list of drugs an insurer will pay for. If a drug is not on a formulary, patients have to pay the full price or substitute another drug, if one is available, which may not work nearly as well. Patients may also try to appeal the insurer’s decision or apply to a company’s patient assistance program.

Scott Matsuda was hit with the formulary problem when his doctor prescribed him a new drug to treat myelofibrosis, a rare type of chronic leukemia. For years, before the drug was developed, his insurance paid for a cocktail of chemotherapy drugs that did little to slow the course of his disease and caused difficult side effects like severe mouth sores.

Then, he entered a clinical trial of Jakafi, a pill that markedly slowed his disease. He did not notice any side effects.

“It was amazing,” Mr. Matsuda said. “I was really happy.”

Three months later, the trial ended, and the F.D.A. approved Jakafi. The daily pills that were saving his life cost $6,000 a month, but Jakafi was not on his insurer’s formulary.

“We were dumbfounded,” Mr. Matsuda said. He and his wife, Jennifer, have a photography business near Seattle, but that price was totally beyond them.

“We are solidly middle-class,” Mr. Matsuda said. “We pay all our bills. We have a good credit score. Six thousand a month would ruin us.”

He went without medications for a few months but eventually returned to the chemotherapy cocktail, suffering fatigue, agonizing bone pain, nausea and mouth sores on top of the steady progression of his leukemia.

He was saved by his oncologist, who suggested that he apply to the PAN Foundation, which helps people with crushing medical bills.

The PAN Foundation assists patients with an annual income about 4 to 5 times the federal poverty level, said Amy Niles, the foundation’s chief advocacy and engagement officer. Those patients, she said, are “usually people who don’t have high incomes, who are falling through the cracks.” The foundation — supported by individuals, charities and drug companies, which can give to a general program but not in order to pay for their own drug — raises hundreds of millions of dollars a year and helps people with any of about 70 illnesses. But the need is so great, Ms. Niles said, “that we are just scratching the surface.”

Patients say they explore every avenue to find help with their medication bills.

Joan Powell, 69, has myelodysplastic syndrome. She said she hunts for foundations and applies for grant after grant because there is no other way to pay for her Reblozyl prescription, which costs $196,303 a year. She said she is on Medicare, which covers most of the price, but she is left with an annual deductible of $8,925. Her yearly income from Social Security and a pension from a company where she used to work adds up to $36,000. She is unable to work.

So far, she has managed to patch together foundation grants, but she worries about how long she can keep that up.

“People just don’t know what you go through,” she said. “If you think about it too much, you get depressed.”

Doctors say they try to help with appeals to insurers, but they do not always succeed.

Dr. Kari Nadeau, an allergist at Stanford Medicine, said the advent of truly effective drugs to treat severe allergies and disfiguring eczema has been bittersweet.

“The world is full for me now, full of hope and promise,” she said. “I can give a patient a biologic and literally see the skin get better right before my eyes.”

But she has spent hours on the phone trying to convince insurers to pay for some of these drugs, with mixed success. And her patients are among the few with resources to seek out a specialist like her.

Harry Levine, an emeritus sociology professor from Queens College, found an unusual way to pay for his drug for the atopic dermatitis, or eczema, that covers most of his body when untreated.

The only thing that helped was steroid creams, but they were not safe to take continuously. So he went through cycles of getting some relief only to watch his eczema return.

Then, in 2017, his doctor told him about, Dupixent, a stunningly effective new drug.

But it cost $36,000 a year, and his insurance would not pay.

Eventually, he was referred to Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who had led studies of the drug and gets samples from the manufacturer, Regeneron. She provides them to Mr. Levine.

But her clinic is self-pay only. Mr. Levine visits her office every two weeks, pays $325 for the visit, and gets a shot — there is no charge for the drug itself. His eczema vanished.

“My skin is now unblemished,” he said. “It’s a miracle.”

Still, $650 a month?

“It’s a heck of a lot cheaper than $36,000 a year,” he said.

.png)

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment